JV dispute over Cu Deposit near Horizontal Falls

In Kestel Superannuation Pty Ltd v Kimminco Pty Ltd ([2024] WAWC 2), the Western Australian Warden’s Court dealt with a multifaceted legal dispute that involved mining joint ventures, and the enforcement of a Settlement Deed that was designed to resolve prior conflicts.

There are questions about the court’s jurisdiction, the obligations of the parties under the Settlement Deed, and whether those obligations were enforceable given the collapse of the joint venture.

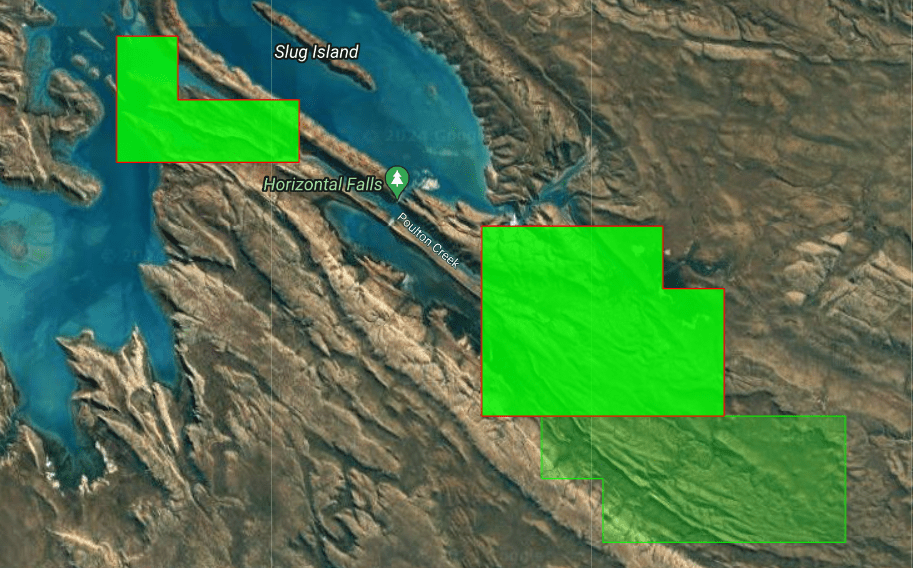

This legal conflict gains further significance when viewed alongside the ongoing copper exploration activities outlined in an ABC article, where Peter Kestel, also a director of McLarty Range Investments (MRI), claims to have made “the biggest copper find since WWII” near Western Australia’s iconic Horizontal Falls. This region, a premier tourist destination, has become a flashpoint between conservation concerns and mining ambitions, with accusations of illegal land clearing adding to the complexity of the situation. These allegations of unlawful clearing on the McLarty Ranges are on the tenements held in a joint venture by the Plaintiff and Respondent.

This case provides valuable insights into how joint venture and settlement agreements are interpreted by courts, as well as the importance of understanding jurisdictional issues in legal proceedings.

Background

The legal conflict began with a joint venture between Kestel Superannuation Pty Ltd (Kestel) and Kimminco Pty Ltd (Kimminco) to develop mining tenements in Western Australia. The venture included multiple stages, with both parties expected to contribute capital and expertise to the project. After disputes arose, the parties signed a Settlement Deed in 2020, under which Kimminco was required to pay Kestel $100,000 as part of the resolution of their initial conflict.

Despite the Settlement Deed, Kimminco refused to pay the $100,000, arguing that its obligation to pay was conditional on the progression of the joint venture, particularly reaching Stage 3, a stage that the project never achieved.

Issue 1: Jurisdiction of the Warden’s Court

A critical early issue in the case was whether the Western Australian Warden’s Court even had jurisdiction to hear the dispute. Jurisdiction refers to the legal authority of a court to hear and decide a case, and in this instance, Kimminco initially raised concerns about whether this court was the appropriate forum for a dispute arising from a Settlement Deed related to a mining joint venture.

The Warden’s Court is a creature of statute, meaning its powers are strictly defined by legislation, in this case, the Mining Act 1978 (WA) (The Act). Specifically, sections 132 and 134 of the Act empower the court to handle disputes related to mining tenements. This raises the question: was the dispute over the $100,000 payment sufficiently connected to mining tenements to fall under the Warden’s Court jurisdiction?

While Kimminco initially questioned the court’s jurisdiction, it later abandoned this argument. Nonetheless, the court proactively sought to address this issue. The Warden emphasized that for the court to hear a matter, the dispute must relate directly to a mining tenement or involve a matter provided for by The Act. In written submissions, Kestel successfully argued that the $100,000 payment was linked to the tenements in question because it was part of the costs incurred during the development of the mining project.

The court ultimately found that the dispute was within its jurisdiction, noting that the Settlement Deed was tied to the joint venture’s operation over the mining tenements. This ruling underscores the importance of understanding how a court’s jurisdiction works, especially in disputes involving specialized courts like the Warden’s Court, which often deal with mining and land-related conflicts.

Kimminco’s Argument: Payment Contingent on Stage 3

Kimminco’s central argument was that the $100,000 payment outlined in the Settlement Deed was not an immediate obligation but was instead contingent on the progression of the joint venture to Stage 3.

The joint venture was structured into four key stages:

Stage 1: Kestel would acquire a 20% ownership in the tenements by paying $140,000 and spending $110,000 on the development of the tenements.

Stage 2: MRI would acquire a 20% share by contributing $350,000 towards the tenements.

Stage 3: MRI would gain another 20% ownership by paying $500,000 to Kimminco and expending an additional $500,000 on the tenements.

Stage 4: MRI would acquire the final 20% by contributing $600,000 in payments and $800,000 in expenditures.

Kimminco contended that since the joint venture did not reach Stage 3—due to the withdrawal of Kestel’s related party, McLarty Range Investments Pty Ltd (MRI)—the obligation to pay the $100,000 never arose.

Kimminco argued that the Settlement Deed should be read in conjunction with the joint venture agreement, meaning that the two documents were inseparable. According to their interpretation, the $100,000 payment would only become due if the joint venture reached Stage 3, and since MRI had withdrawn, this condition was never met. In their view, the liability for the payment never crystallized.

Court’s Decision

The court rejected Kimminco’s argument and ruled that the $100,000 payment under the Settlement Deed was a separate, enforceable obligation. The court concluded that the Settlement Deed was designed to resolve a past dispute and was not dependent on the future success of the joint venture. According to the court, the deed created an immediate liability at the time of its signing in 2020, and Kimminco’s failure to make the payment was a breach of this agreement.

In its reasoning, the court emphasized that the Settlement Deed was a standalone agreement meant to settle disputes related to the joint venture. Even though the joint venture collapsed before reaching Stage 3, the court found that this had no bearing on Kimminco’s obligation to pay the $100,000, which was part of the settlement arrangement.

Key Takeaways: Understanding Jurisdiction and Reading the Fine Print is Crucial to Protecting Your Tenements

This case highlights two essential lessons for mining companies in Western Australia: understanding jurisdiction and carefully reading the fine print in your agreements, both of which are critical for protecting your tenements.

- Know the Right Court: The Warden’s Court has specific authority under The Act to handle tenement-related disputes. Ensuring your case falls under its jurisdiction is key to protecting your rights. Bringing disputes to the correct forum can save time and protect your interests in mining projects.

- Read the Fine Print: Misinterpreting contractual obligations, as seen in Kimminco’s case, can lead to costly legal battles. It’s vital to understand your commitments in joint ventures and settlement agreements to avoid breaching contracts and risking your tenements.

- Compliance is Critical: Staying compliant with both your agreements and mining regulations helps prevent disputes that could jeopardize your tenements. Ensuring you know when obligations are triggered can protect your investments.

Understanding jurisdiction and the fine details of your contracts are key to safeguarding your mining interests. Our training programs help companies navigate WA’s mining compliance landscape with confidence.

Conclusion

Businesses involved in joint ventures, must ensure they are fully aware of the legal frameworks governing their projects and the obligations set out in agreements like settlement deeds. In this case, Kimminco’s failure to grasp its obligations under the Settlement Deed resulted in an unfavourable legal outcome, emphasizing the critical need to understand when and how liabilities arise.

Our training programs are designed to help companies navigate these complexities. By providing in-depth knowledge of mining regulations, jurisdictional issues, and the nuances of tenement management, we equip businesses with the tools they need to protect their tenements and avoid costly legal pitfalls.

With our guidance, you’ll be better prepared to manage compliance and safeguard your mining investments in Western Australia.

Upcoming courses:

Advanced Tenement Management: October 24-25, 2024

Practical Tenement Management: November 7-8, 2024

Tenement Literacy 101: October 17, 2024

Understanding Tenement Expenditure: November 28-29, 2024